Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

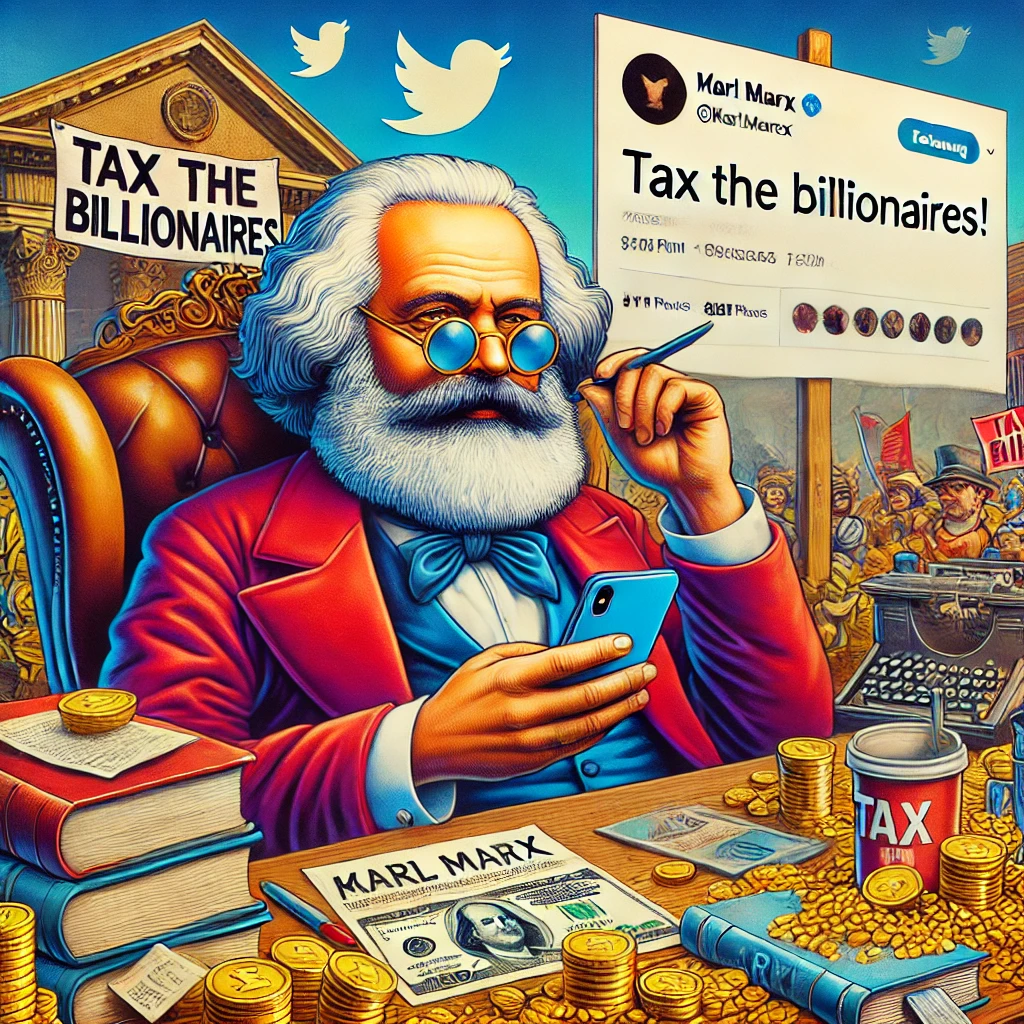

Is Karl Marx really the bogeyman he’s made out to be? This humorous yet thoughtful exploration debunks myths, examines why ‘Marxism’ is a catch-all insult today, and highlights the values we can still learn from his work.

Karl Marx: the name alone is enough to spark spirited debates, eye rolls, or a Twitter thread spiralling out of control. For a 19th-century philosopher who spent much of his time buried in books and dodging landlords, Marx has managed to become one of the most polarising figures in modern discourse. In some circles, his work is revered as gospel. In others, the mere mention of his name is enough to conjure fears of red flags, gulags, and collective farms.

Yet, most of the vitriol hurled at Marx has little to do with what he actually said. In today’s cultural zeitgeist, “Marxism” has become a catch-all insult, particularly on social media and in certain corners of the political arena. Suggest taxing billionaires? That’s Marxist. Advocate for free school meals? A Marxist ploy. Think public libraries are worth funding? Comrade, your hammer and sickle await. And this trend isn’t limited to anonymous Twitter accounts. Public figures like Donald Trump, Elon Musk, Boris Johnson, and even Liz Truss have all, at various points, leaned on this caricature of Marxism to dismiss ideas they don’t like.

To understand why Marx gets dragged into everything from debates about universal healthcare to lettuce shelf lives, we need to delve into what he actually argued, why his ideas still resonate, and how he’s been misrepresented to the point of absurdity.

If Marx were alive today, he’d likely be horrified—not just by the state of late capitalism, but by how thoroughly his work has been misunderstood. Contrary to popular belief, Marx wasn’t a cheerleader for authoritarian regimes. He didn’t invent communism, and he certainly didn’t suggest that the best way to run an economy was to nationalise everything down to the corner shop. What Marx did do was critique capitalism as a system that prioritises profit over people, perpetuates inequality, and alienates workers from their labour.

Alienation is one of Marx’s most profound and surprisingly relatable concepts. He argued that in capitalist systems, workers are separated from the products of their labour, the process of production, their colleagues, and even themselves. This idea might sound abstract, but it’s eerily tangible. Ever spent hours on a tedious project, only to feel like it didn’t matter? That’s alienation. Ever felt like your job defined you but didn’t fulfil you? Alienation again. Marx’s critique wasn’t about tearing down society—it was about pointing out the cracks in its foundation.

But in today’s discourse, nuance often takes a backseat to name-calling. Right-wing commentators and politicians frequently invoke Marx’s name as a rhetorical weapon. In the British press, the word “Marxist” is wielded like a verbal Molotov cocktail, hurled at anyone who so much as hints at progressive policies. Suggest better funding for the NHS? Clearly, you’re a Marxist plotting to abolish private property. Question the fairness of CEO pay compared to that of workers? Straight to the gulag for you, comrade.

It’s not just the press. Figures like Donald Trump and Elon Musk have turned “Marxist” into shorthand for “anyone who mildly inconveniences me.” Trump, in particular, has a flair for conflating all left-leaning policies with Marxist conspiracies, painting universal healthcare and social safety nets as stepping stones to the collapse of Western civilisation. Musk, meanwhile, has taken to Twitter (or X, if you’re feeling generous) to mock progressive tax policies and wealth redistribution as if they’re precursors to a dystopian workers’ revolution. For Musk, who once tweeted that he was “accumulating resources to help humanity,” any suggestion of taxing those resources feels, well, a bit Marxist.

Closer to home, Boris Johnson has deftly used the spectre of Marxism to deflect criticism of his own policies. Climate activists, union strikes, and even moderately progressive economic proposals have all been dismissed as radical left-wing or Marxist threats to British tradition. And let’s not forget Liz Truss, who managed to position herself as the last defender of free-market economics during her brief stint as Prime Minister. Truss’s infamous “anti-growth coalition” rhetoric seemed to imply that anyone questioning her policies was a Marxist trying to sabotage the economy. Ironically, it wasn’t Marxism but her own trickle-down plans that led to one of the most dramatic economic collapses since, well, Marx first picked up a pen.

But why is Marxism used this way? Part of the answer lies in its historical baggage. The 20th century saw Marx’s ideas co-opted and distorted by authoritarian regimes, from the Soviet Union to Maoist China. These associations have made it easy for critics to dismiss Marx wholesale, conflating his critique of capitalism with the worst excesses of those regimes. It’s a bit like blaming Darwin for social Darwinism or Newton for someone dropping an apple on your head.

Another reason lies in the simplicity of the label. Calling someone a Marxist is a quick, effective way to shut down debate. It requires no engagement with the actual ideas being proposed—just a swift accusation that ties them to an ideological bogeyman. In a world of soundbites and clickbait, nuance is often the first casualty.

Yet, despite the vitriol, Marx’s ideas remain strikingly relevant. His analysis of inequality, alienation, and the commodification of life feels almost prophetic in the age of gig work, social media influencers, and billionaire space races. Take his concept of surplus value—the idea that the profits generated by workers are pocketed by capitalists. In today’s terms, it’s why CEOs can make 400 times the salary of their average employee, or why the wealthiest 1% hold more than half the world’s wealth.

Even Marx’s critique of consumer culture seems eerily prescient. He wrote about how capitalism commodifies everything, turning even our leisure time into opportunities for profit. In the 21st century, this looks like hobbies becoming side hustles, friendships monetised through social media, and the relentless pressure to turn every passion into a personal brand. It’s a system where even your most intimate moments are opportunities for engagement metrics.

So, what can we actually learn from Marx? For one, his work encourages us to ask who benefits from the systems we participate in. Why do billionaires exist in a world where poverty persists? Why do we accept that some people must work multiple jobs just to survive, while others profit from owning assets? These aren’t revolutionary questions—they’re moral ones.

Marx also reminds us to value labour not just for its economic output, but for its human contributions. Work, at its best, can be a source of pride, community, and meaning. At its worst, it can be alienating, exploitative, and soul-crushing. Recognising this distinction is crucial, especially in a world where hustle culture glorifies overwork and burnout.

Of course, Marx wasn’t perfect. His writing is dense, his predictions didn’t always pan out, and his solutions often raise more questions than they answer. But dismissing him entirely because of how his ideas have been misused is like throwing out a good book because someone dog-eared the pages. Marx’s critiques remain a valuable lens for examining the world, even if his solutions aren’t always applicable.

In the end, the problem isn’t Marx—it’s the way we talk about him. He’s not a bogeyman or a saint. He’s a thinker, one who grappled with big questions about fairness, power, and humanity. If we can look past the caricatures and memes, there’s a lot to learn from his work.

And if that makes me a Marxist, so be it. Just don’t expect me to grow out the beard.