Having spent ten years as a local councillor, working in and for the community, I was appalled by how little help exists for those who are right at the bottom, but also for those in the mid-band—people who do not qualify for benefits yet struggle to meet their basic needs on low earnings, a system that actively and perversely discourages self-improvement and self-learning where earning more leads to disproportionately increased costs and decreased benefits. This experience provided insight into how social support is structured in the UK and how various forms of assistance operate within an increasingly strained welfare state.

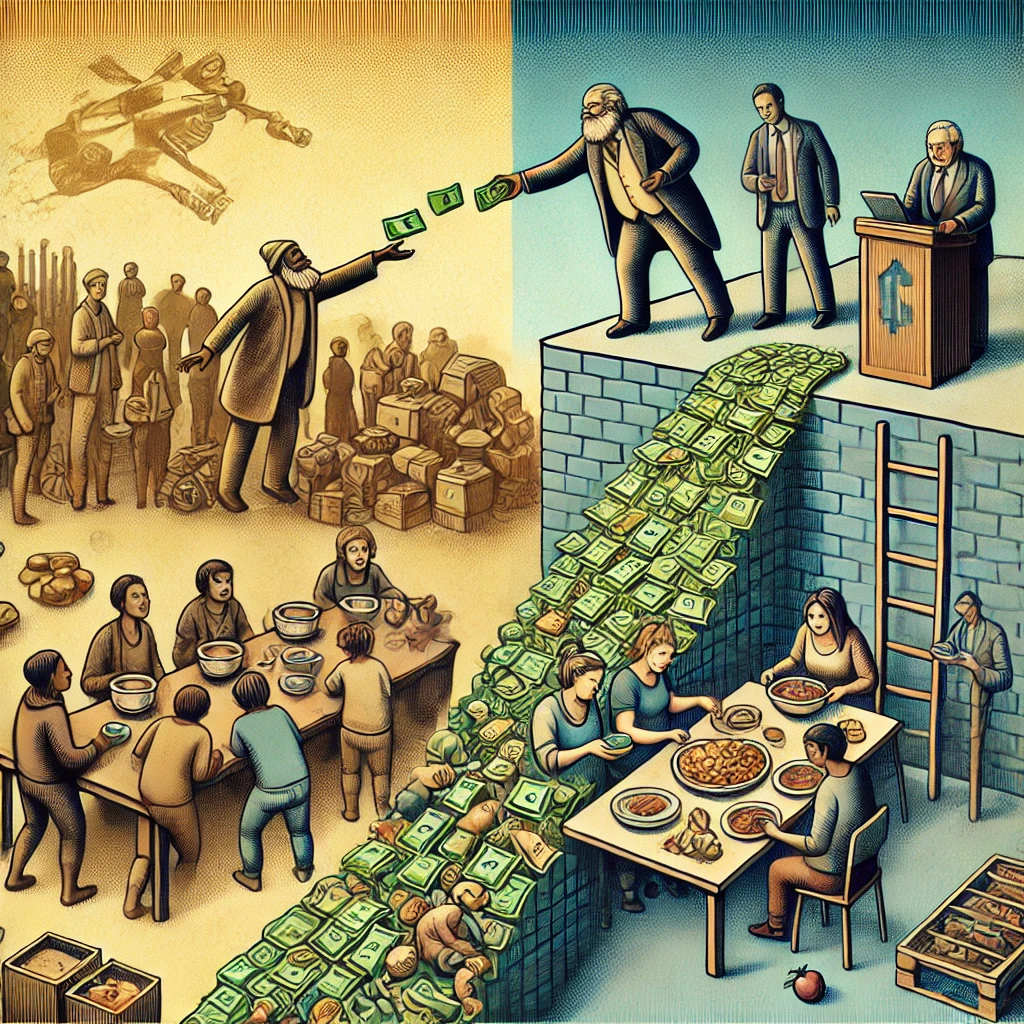

A well-known proverb states, “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” This phrase highlights a key sociological debate: should social intervention focus on immediate relief, or should it address the deeper, structural causes of inequality? Mutual aid and charity represent two different approaches to this issue. While both play an important role in society, their impact, structure, and outcomes differ significantly.

What is Charity? A Hierarchical Approach to Helping

Charity is one of the most widely recognised forms of social assistance in the UK. It is rooted in philanthropic traditions where those with resources provide aid to those without. This model is seen in institutions such as food banks, homeless shelters, and large charitable organisations like the Trussell Trust and Shelter. While charity provides essential support, sociologists question whether it fundamentally addresses the causes of poverty or merely treats its symptoms.

Key Characteristics of Charity:

- Top-Down Structure – Charitable giving typically involves a hierarchical relationship, where assistance flows from donors to recipients without necessarily engaging the latter in decision-making.

- Short-Term Relief – Charity focuses on immediate needs, such as food and temporary housing, but does not address systemic issues like low wages, insecure work, or housing shortages.

- Perpetuation of Dependence – Critics argue that charity, while well-intentioned, can create dependency rather than foster long-term self-sufficiency.

Strengths of Charity

Despite its limitations, charity is crucial in addressing urgent needs, particularly during crises and disasters. Following floods, economic downturns, and public health emergencies, charities provide rapid, life-saving assistance that government bodies often fail to deliver quickly. Sociologists examining social capital (Putnam, 2000) argue that charitable organisations contribute to social cohesion and provide psychological and material support to distressed individuals.

Furthermore, some charitable models integrate long-term solutions by combining direct aid with advocacy and policy work, pressuring governments to enact systemic reforms. Organisations such as Shelter provide housing support and campaign for rent controls and tenant rights, demonstrating a hybrid approach between charity and mutual aid.

What is Mutual Aid? A Community-Based Model of Support

Mutual aid differs from charity in that it is solidarity-based rather than hierarchical. It operates on cooperation and reciprocal exchange principles, where individuals and communities work together to meet shared needs without relying on external benefactors.

Mutual aid networks have a long history, particularly among marginalised communities who have been excluded from formal support systems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, thousands of mutual aid groups emerged across the UK to support vulnerable individuals by providing food, medicine, and financial assistance. These grassroots efforts highlighted how mutual aid can fill the gaps left by inadequate government responses (Spade, 2020).

Key Characteristics of Mutual Aid:

- Community-Led & Horizontal – Unlike charity, mutual aid initiatives are organised collectively, often without a formal leadership structure.

- Direct Action & Empowerment – Participants actively contribute and benefit from mutual aid networks, fostering self-reliance and community resilience.

- Structural Awareness – Mutual aid acknowledges that social problems stem from systemic inequalities and seeks to address them collectively.

Challenges of Mutual Aid: Burnout and Sustainability

One major issue I observed both as a councillor and a volunteer is that mutual aid efforts tend to rely on the same core group of people, leading to burnout among organisers. Unlike charity, which often has paid staff, mutual aid depends heavily on unpaid labour, which can be unsustainable over the long term. While mutual aid builds resilience and solidarity, it struggles to scale effectively without institutional support or sustainable funding.

Sociologists studying mutual aid praxis argue that, despite its principles of equality, mutual aid groups frequently experience internal tensions, where the burden falls disproportionately on a few dedicated individuals (Kenworthy et al., 2023). While effective at responding to crises, these groups often lack long-term sustainability mechanisms, leading to volunteer exhaustion and eventual dissolution.

Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid Theory (Glassman, 2000) offers an alternative view, suggesting that cooperation is a natural evolutionary advantage rather than a utopian ideal. This historical perspective supports the argument that mutual aid is not just an emergency measure but a fundamental form of social organisation that challenges hierarchical state structures.

The Role of Government: Indifference and Impotence?

One of the most pressing concerns in the UK is the lack of government intervention in tackling systemic issues. Austerity policies since 2010 have drastically reduced funding for public services, leaving local councils struggling to meet community needs. Between 2010 and 2020, local government funding was cut by over 50% (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2021). This has forced local authorities to depend on charitable organisations, which increasingly fill the role of social safety nets.

At the same time, initiatives such as levelling up, which aimed to reduce regional disparities, have been criticised for allocating funds in ways that do not always reflect actual deprivation levels. Some of the areas receiving investment had relatively stable economic conditions, whereas some of the most deprived communities saw little meaningful support. Well-established metrics, such as the Indices of Multiple Deprivation, enable the government to identify the areas most in need. Yet, funding allocations often seemed politically motivated rather than driven by actual need, reinforcing structural inequalities (Dorling, 2022).

Additionally, sociologists examining welfare retrenchment argue that this shift is not accidental—governments often appropriate the language of mutual aid to justify the withdrawal of social safety nets (Mould et al., 2022). This rhetorical shift reframes welfare as an individual or community responsibility, absolving the state of its role in providing universal protections.

Local government, meanwhile, is left politically and financially constrained. While councils are expected to tackle social issues, their ability to do so is severely limited by financial restrictions and bureaucratic hurdles. Even well-intentioned initiatives often fail due to a lack of sustained funding and the need to navigate an overly complex administrative process.

Conclusion: Rethinking How We Address Social Problems

While charity and mutual aid both address social needs, their effectiveness and long-term impact differ. A sustainable future requires a hybrid approach, where mutual aid principles of solidarity and empowerment are supported by systemic policy changes to reduce reliance on crisis-driven charity. If governments remain unwilling to address structural inequalities, communities will continue to rely on volunteer-led efforts despite their inherent limitations. Moving forward, a combination of grassroots organising, government intervention, and sustainable welfare policies will be essential in shifting from crisis management to long-term social justice.