Deepfake technology has sparked widespread ethical and legal debates, particularly when used in non-consensual pornography. These computer-generated videos superimpose someone’s face onto explicit content, raising serious concerns about consent, privacy, and autonomy. Some argue deepfakes fall under free expression, while others see them as a dangerous violation of individual rights that reinforces harmful gendered power structures (Citron & Franks, 2014).

In this piece, we take a sociological look at deepfake pornography—its implications for consent, agency, power, and broader social norms. Using feminist theory, media ethics, symbolic interactionism, Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic violence, and social contract theory, we explore the moral landscape of this controversial technology.

Examining the Debate: Is Deepfake Pornography a Victimless Crime?

Some argue that deepfake pornography does not cause direct harm, claiming it is purely digital and, therefore, distinct from traditional forms of sexual exploitation. Proponents suggest that, much like fictionalised adult content, deepfakes should be viewed as artistic expression or fantasy rather than an act requiring ethical or legal scrutiny. These arguments highlight key debates around autonomy, consent, and digital rights, but they also raise questions about the broader implications of this technology on social norms and personal agency.

The Key Arguments—Where They Stand and Where They Fall Short:

- “No Physical Harm” – Defenders claim that because no real-world interaction occurs, deepfakes do not constitute direct harm. However, research indicates that victims experience psychological distress, reputational harm, and professional setbacks, undermining the idea that harm must be physical to be significant (Citron, 2019).

- “Freedom of Expression” – Some argue that deepfakes fall under digital artistic liberties. While some scholars and legal advocates highlight the potential of deepfake technology for creative and expressive purposes, its application in non-consensual pornography raises complex legal and ethical concerns. The First Amendment Encyclopedia notes that, despite their misleading nature, deepfakes are protected under the US First Amendment as a form of free expression. However, legal scholars debate the extent to which freedom of expression protections should apply when deepfake content infringes on personal rights and autonomy. Legal cases have begun to address these conflicts, highlighting the tension between digital creativity and privacy rights (Chesney & Citron, 2019). For instance, the First Amendment Encyclopedia notes that, despite their misleading nature, deepfakes are protected under the First Amendment as a form of free expression. However, when someone’s likeness is used without their permission, this shifts into non-consensual exploitation, challenging the ethics of unrestricted creative expression. While freedom of expression is a core democratic principle, it must be weighed against individuals’ rights to control their own likeness and bodily representation. Feminist scholars argue that non-consensual deepfake pornography functions as a form of gendered violence, where digital spaces become extensions of patriarchal control (Citron, 2019; Ringrose et al., 2021).

- “Legal Grey Areas” – Since laws regarding digital likenesses remain underdeveloped, some claim deepfake pornography exists in a legal limbo. However, this highlights an urgent need for updated legislation rather than an ethical justification for its existence (Ringrose et al, 2021).

- “It’s Just Fantasy” – Proponents argue that deepfakes exist in a purely digital realm, much like animation or fictionalised erotica. Yet, studies show that exposure to such content can normalise non-consensual behaviour and influence societal attitudes toward privacy and consent (Fraser, 2013; Ringrose, 2021).

- “Harm Reduction” – A utilitarian view suggests that deepfake pornography could divert demand from real-world exploitation. Some researchers in media psychology argue that controlled fantasy consumption, including synthetic adult content, may provide a safe outlet for desires that might otherwise contribute to harm. However, the empirical evidence remains contested, and critics point out that the normalisation of digital exploitation may reinforce problematic attitudes rather than reduce harm (McGlynn & Rackley, 2020; Fernandes, 2019). However, this assumption lacks strong empirical support, and some studies indicate that the normalisation of digital exploitation may actually reinforce problematic attitudes (McGlynn & Rackley, 2020).

While these arguments offer a perspective on deepfake pornography as a new and evolving technology, they fail to account for its broader social consequences fully. The real question is: who benefits from deepfake pornography, and who bears the consequences?

Power and Control: A Bourdieuian, Intersectional, and Feminist Perspective on Deepfake Pornography

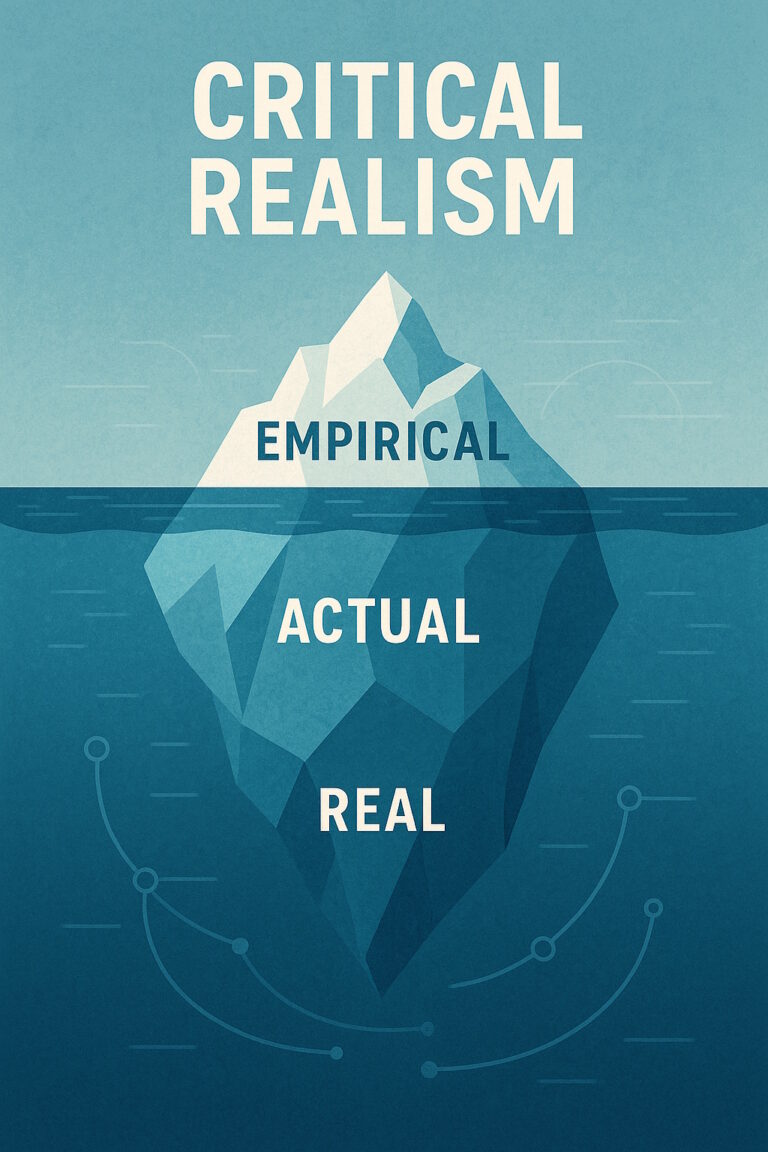

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence helps us understand how deepfake pornography reinforces existing power imbalances. Symbolic violence refers to how social structures normalise inequalities, making them seem natural or inevitable (Bourdieu, 1991). However, this analysis can be further enriched by exploring Sarah Banet-Weiser’s (2018) concept of digital patriarchy, which describes how online spaces reproduce offline gendered hierarchies, reinforcing male control over women’s digital identities.

The Structural Impact of Deepfake Pornography:

Deepfake pornography does not impact all individuals equally. Intersectional feminist scholars argue that women of colour, LGBTQ+ individuals, and economically disadvantaged women often face heightened vulnerabilities to digital exploitation. These groups are more likely to be targets of non-consensual deepfake content and experience intensified social and professional consequences due to existing structural inequalities (Crenshaw, 1991; Noble, 2018).

- Gendered Exploitation – The majority of deepfake pornography targets women, particularly public figures, reinforcing male dominance in digital spaces (Ringrose, 2021).

- Erosion of Consent – The widespread presence of deepfake pornography weakens societal understandings of consent, reshaping privacy norms in disturbing ways (Citron, 2019). Ringrose (2021) further argues that this shift in digital culture normalises a form of technologically mediated sexual violence, wherein consent is increasingly disregarded as a social norm.

- The Commodification of Identity – The digital age has turned personal images into currency. Deepfake pornography exemplifies this process, where specific identities are consumed and exploited for profit without consent. Banet-Weiser (2018) argues that this reflects a broader pattern of digital patriarchy, where women’s images are not only monetised but also weaponised to exert control over their public and private lives (Fraser, 2013). She contends that the visibility of women online does not equate to empowerment but instead exposes them to new forms of commodification and exploitation. Fraser (2013) complements this argument by highlighting how neoliberal capitalism exploits feminist rhetoric, offering the illusion of empowerment while maintaining deeply ingrained structural inequalities. She argues that corporate-backed consent-awareness campaigns and regulatory frameworks often focus on individual responsibility rather than addressing the systemic power structures that enable digital sexual exploitation in the first place. In the case of deepfake pornography, these forces converge, reinforcing existing gendered hierarchies under the guise of technological progress and digital freedom.

The Real-World Impact: A Look at Victims’ Experiences

The conversation around deepfake pornography isn’t just theoretical—it has real, tangible consequences for those affected:

- Victims experience emotional distress, reputational damage, and increased vulnerability to harassment (Citron, 2019; Ringrose, 2021). Studies indicate that the psychological toll of non-consensual deepfake pornography mirrors that of real-world sexual violence, further demonstrating its impact on victims.

- Women and marginalised groups are disproportionately targeted, reinforcing existing inequalities in digital and public life (Ringrose, 2021). Ringrose’s research highlights that women subjected to deepfake pornography often experience long-term career damage and social ostracisation, further entrenching gendered disadvantages in both professional and personal spheres.

- Studies on digital sexual violence show that victims often face professional repercussions, blackmail, and social stigma (McGlynn & Rackley, 2020). Citron (2019) also underscores the inadequacy of current legal frameworks in addressing these issues, arguing for more robust protections to prevent digital exploitation.

Sociological inquiry isn’t about picking sides; it’s about understanding power, agency, and the structures shaping our digital world. Recognising the impact on victims ensures we aren’t discussing these issues in an abstract vacuum.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Deepfake pornography sits at the intersection of digital freedom, ethics, and structural power. The justifications offered for its existence often fail to acknowledge the deeper implications for privacy, consent, and digital identity.

So, what’s next? There’s no simple answer, but sociologists, ethicists, and policymakers need to grapple with key questions:

- How do we regulate deepfake technology without overreaching into creative digital expression?

- What role should technology companies and social platforms play in moderating harmful content?

- How do deepfake technologies shape broader cultural understandings of consent and bodily autonomy?

Rather than offering easy solutions, sociological analysis pushes us to interrogate how emerging technologies influence power, ethics, and individual rights. While deepfake pornography raises serious ethical concerns, debates around free expression and digital creativity remain ongoing, requiring further discussion among scholars, policymakers, and the public. As digital representation becomes increasingly fluid, deepfake pornography forces us to rethink the boundaries between free expression, exploitation, and ethical digital citizenship.