Modern education stands at a crossroads. Once envisioned as a transformative force for individual and societal advancement, it has increasingly been reduced to a mechanism for credential accumulation. Schools, colleges, and universities emphasise qualifications, certificates, and rankings over meaningful engagement, reflection, and personal development. This shift reflects broader societal changes where knowledge has become commodified, and credentials operate as both currency and gatekeeper in an intensely competitive labour market.

Yet the deeper sociological question remains: what should education truly be for? Is its highest purpose to rank individuals and ration opportunities, or to cultivate capabilities for human flourishing, critical citizenship, and social change? Drawing on critical theories of social reproduction, recognition, and bounded agency, this article interrogates the rise of credentialism, explores the marginalisation of experiential learning, and argues for a fundamental reimagining of education’s role. At stake is not merely how we measure achievement, but how we conceptualise equity, opportunity, and the very meaning of education itself.

Credentialism: Education as Social Closure

The increasing dominance of credentialism within modern education has sparked an urgent need to re-evaluate the true purpose of learning. Once seen as a means of holistic development, education is now overwhelmingly framed as a competitive race for qualifications, certificates, and formal recognition. This credential-driven culture not only narrows the purpose of education but actively undermines experiential forms of learning that nurture critical thinking, resilience, creativity, and meaningful skill development. In reclaiming education’s true purpose, we must critically assess how credentialism reproduces existing social hierarchies, marginalises non-traditional learners, and perpetuates structural inequality.

Credentialism, as conceptualised by Randall Collins (1979) and critiqued within broader sociological traditions, serves as a mechanism of social closure: qualifications function less to denote genuine competence and more to restrict access to scarce opportunities. Historically, credentialism emerged as an attempt to create standardised, seemingly objective measures of ability in response to nepotism and favouritism. However, this well-intentioned aim has calcified into a system that reproduces inequality. This stratification ensures that access to the most prestigious qualifications — and by extension, elite employment and social mobility — remains disproportionately reserved for the already advantaged. Under this model, education transforms from a vehicle of empowerment into a gatekeeping institution. Rather than developing skills and knowledge for their own sake, students are taught to pursue credentials as ends in themselves, a process that aligns with Bourdieu’s (1986) theory of social reproduction through cultural capital.

Experiential Learning: A Relational Alternative

Experiential learning, by contrast, emphasises process over product. Rooted in the philosophies of John Dewey (1938) and later expanded by Kolb (1984), experiential education values active engagement, reflection, and the application of learning to real-world contexts. It fosters not only cognitive development but also emotional and social growth, cultivating capacities that are increasingly necessary in a rapidly changing world: adaptability, collaborative skills, ethical reasoning, and creative problem-solving. Experiential learning draws upon a relational model of education where knowledge is socially constructed and meaningfully contextualised. While it holds great potential, experiential learning is not without challenges; quality can vary widely, and access to rich experiential opportunities is itself often stratified.

Yet, despite its proven benefits, experiential learning remains institutionally undervalued. Policy frameworks continue to prioritise standardised testing, league tables, and narrow academic attainment measures, reinforcing a view that only formally credentialed knowledge is legitimate. This hierarchy delegitimises diverse forms of expertise acquired outside traditional classroom settings, further entrenching systemic inequalities. As Fraser (2000) highlights, struggles for recognition are fundamental to achieving participatory parity. Experiential learning’s frequent marginalisation is not merely a pedagogical oversight; it constitutes a structural injustice.

Spatial Inequality and Bounded Educational Pathways

Credentialism not only stratifies individuals based on educational attainment but also intensifies existing spatial inequalities across geographic regions. Particularly, it disadvantages rural, remote, and socio-economically marginalised communities, where access to prestigious educational institutions is often limited or non-existent (Corbett, 2007; Reay, 2017). Individuals living in such areas encounter multiple barriers: reduced financial resources, limited cultural capital, and physical distance from elite centres of learning, all of which compound disadvantage. Urban-centric policies that prioritise standardised credentials tend to ignore the socio-spatial dynamics that shape educational opportunities, inadvertently reinforcing rural marginalisation.

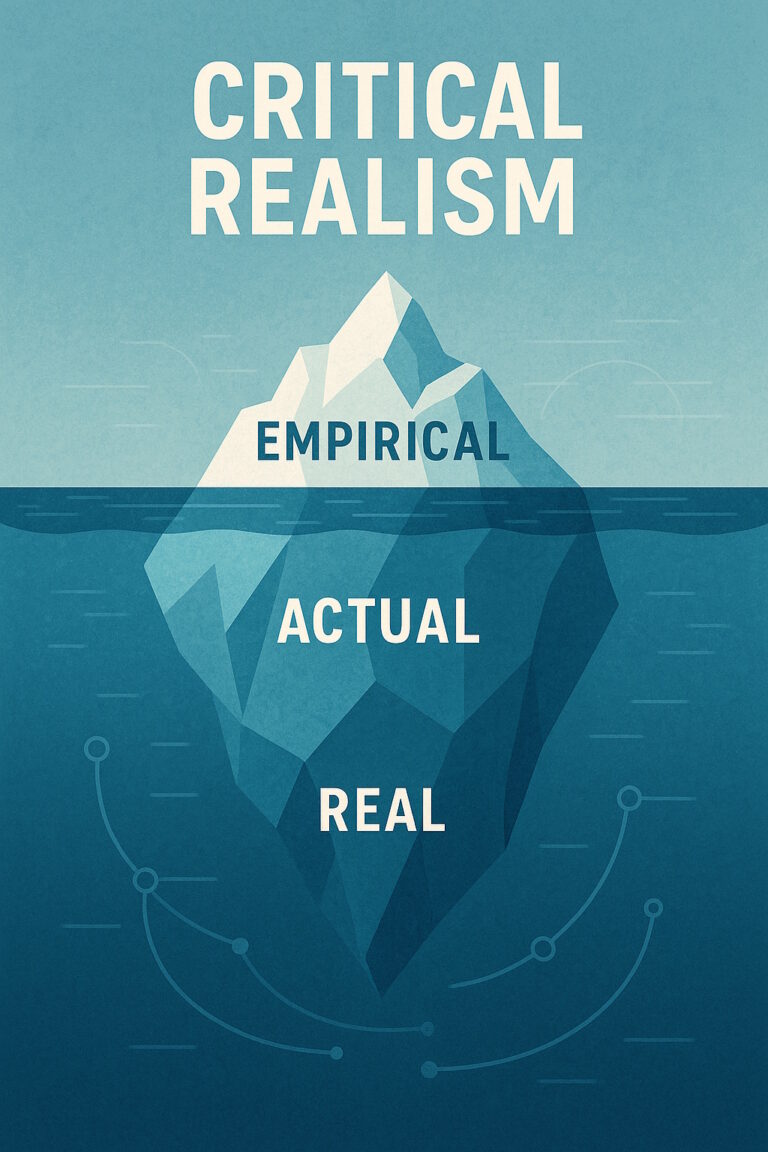

Experiential learning, when rooted in local contexts, offers a promising but complex corrective. Embedded community projects, field-based apprenticeships, and context-sensitive learning initiatives can empower learners by linking educational content directly to lived experiences and local needs. These models foster authentic skill development and encourage a stronger sense of belonging and agency. However, as critical realist perspectives (Bhaskar, 1979; Archer, 2003) emphasise, agency is not absolute. Even with innovative localised educational approaches, broader structural forces — including funding inequalities, labour market restructuring, and cultural misrecognition — significantly delimit individuals’ capacity to leverage experiential learning into social mobility.

Thus, while experiential learning holds transformative potential, its impact is fundamentally conditioned by wider socio-economic and spatial structures. A sociologically grounded reform agenda must acknowledge that without addressing the systemic barriers that constrain educational and occupational opportunities across different regions, experiential approaches risk becoming another bounded, context-dependent form of advantage accessible to only a select few.

Moreover, credentialism exacerbates spatial inequalities, particularly disadvantaging rural and socio-economically marginalised groups (Corbett, 2007; Reay, 2017). Access to prestigious credentials often demands financial resources, cultural familiarity, and geographic proximity to educational power centres. Experiential learning, especially when embedded within local communities, offers a critical corrective: it enables skill development tailored to real contexts and needs, fostering a more authentic and grounded form of empowerment. However, as critical realist perspectives (Bhaskar, 1979; Archer, 2003) remind us, such opportunities are not exercised within a vacuum. Agency is bounded; structural conditions significantly delimit the transformative potential of experiential pathways.

The Myth of Meritocracy in Modern Education

Education policy discourses often cling to the ideology of meritocracy — the belief that success is a product of individual effort and ability (Littler, 2017). However, sociological critiques (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977; Reay, 2017) demonstrate that this narrative obscures structural inequalities and legitimises privilege. Credentialism functions as a symbolic mechanism of meritocratic misrecognition (Fraser, 2000), disguising inherited advantage as personal achievement while devaluing alternative forms of skill and knowledge production.

Reclaiming Education’s True Purpose

Reclaiming education’s true purpose requires a fundamental shift. Formal education must move beyond credential accumulation towards valuing broader forms of learning and recognising multiple pathways to success. Schools and universities should integrate experiential portfolios into admissions processes, formally accredit service learning and field-based projects, and embed reflective learning models throughout curricula. Assessment frameworks must evolve to capture the breadth and depth of learning experiences, moving beyond the sterile metric of exam performance.

Importantly, we must also acknowledge the pragmatic appeal of credentialism: in large, complex societies, credentials have offered a seemingly efficient mechanism to assess and sort individuals. However, in a knowledge economy marked by complexity and unpredictability, this mechanism has become increasingly blunt, rigid, and exclusionary.

Crucially, this reclamation must engage with the politics of recognition. Experiential learning must not only be included but recognised as legitimate and valuable in its own right. Fraser’s ( 2000) notion of recognition justice demands institutional reforms that valorise diverse forms of knowledge and experience, challenging the hegemony of credentialism.

Ultimately, education must be reimagined as a lifelong, life-wide process. In a society increasingly characterised by complexity and uncertainty, rigid credentialism offers diminishing returns. Experiential learning equips individuals not merely to navigate the world as it is, but to actively shape the world as it could be. Reclaiming education’s true purpose is not a nostalgic plea for a lost ideal; it is a sociological imperative for a just and sustainable future.