The authority of expertise, once embedded in the institutional structures of modernity, has become increasingly unstable. From medical science to legal judgment, the public performance of doubt and defiance now permeates digital and physical discourse alike. It is no longer uncommon for individuals to claim—often with profound certainty—that they know more about virology than the Chief Medical Officer or more about constitutional law than the Supreme Court. Such assertions are often met with celebration and affirmation in the echo chambers of social media by like-minded peers, but beneath the surface lies a complex sociological phenomenon: a collapse not of knowledge per se, but of trust in the institutions that produce, validate, and disseminate it.

This article explores the sociological underpinnings of that collapse. It does not simply lament the spread of misinformation or mock those who challenge expert consensus—though, as recent cultural trends suggest, mocking the ‘boffins’ and ‘eggheads’ has become something of a national pastime. Rather than reinforcing this derision, the aim here is to understand why such contempt for expertise has become so socially acceptable, and what that tells us about shifting cultural norms and institutional legitimacy. Instead, it asks: what structural conditions make such challenges both possible and appealing? And how might expertise be reimagined in a cultural context where epistemic legitimacy is deeply contested? Through a lens grounded in symbolic power, digital sociology, and the reflexive critique of knowledge systems, this article aims to map the contours of our epistemic disarray.

Individualism, Comparison, and Conditional Empathy

Another dimension of this shift is the broader cultural move from collective responsibility to individualistic orientation. Late modern societies, particularly in neoliberal contexts, increasingly valorise self-sufficiency, autonomy, and competition. In such a climate, appeals to community or solidarity often appear suspect, unless they can be reframed as personal grievance or comparison.

This helps explain a recurrent rhetorical trope: the invocation of homeless veterans or struggling pensioners only in juxtaposition with immigrants, asylum seekers, or benefit recipients. These comparisons rarely emerge from a place of consistent concern for marginalised citizens. Instead, they operate as moral signalling—expressions of conditional empathy that function primarily to police social boundaries. As Tyler (2013) notes, such discourses of ‘deservingness’ are central to the cultural politics of welfare and belonging. The visibility of one group’s suffering is amplified not to solve it, but to delegitimise another group’s claim to support.

In this framework, social empathy becomes zero-sum. The plight of the homeless soldier is meaningful only insofar as it can be weaponised against the refugee or migrant. Yet when not invoked for comparative outrage, these same individuals—soldiers, the homeless, the elderly—often fade into invisibility. Their suffering is not the issue; their symbolic utility is. This pattern reflects a profound erosion of collective identification, one where the only form of solidarity that survives is exclusionary.

By locating morality in opposition rather than relation, such discourses reinforce epistemic tribalism: the idea that only “our” people suffer rightly, and only “they” receive undue sympathy. This further destabilises shared truth, as facts become secondary to the moral scripts into which they are slotted.

Expertise, Symbolic Capital, and the Politics of Recognition

Weber (1978) described modern authority as rational-legal, grounded in codified expertise and institutional legitimacy. Yet as Bourdieu (1986) shows, such legitimacy depends not only on knowledge but on symbolic capital: the recognition of authority by others. Expertise is thus always relational. Those who speak from within credentialed spaces rely on a tacit social contract: that their knowledge will be acknowledged as valid and their status as experts respected.

This contract has frayed. For many, especially those structurally excluded from educational or professional pathways, the symbols of expertise appear arbitrary or elitist. Lareau (2003) illustrates how middle-class families inculcate institutional fluency in their children, preparing them to engage with and benefit from expert systems. By contrast, working-class individuals often lack the cultural capital required to navigate these same systems, fostering alienation rather than trust. When the rules of expert communication are opaque or exclusive, suspicion becomes a reasonable stance.

Moreover, the rise of populist discourse—emphasising the wisdom of the ‘ordinary person’ over the claims of professionals—has weaponised this alienation. Experts are no longer seen as public servants but as technocratic gatekeepers. When political leaders echo this scepticism, they confer legitimacy upon anti-expert sentiment, making it not just acceptable but laudable.

Importantly, some criticisms of expert communities are not only understandable but justified. Failures in economic forecasting—such as the inability to predict the 2008 financial crisis—have damaged the credibility of entire disciplines. In healthcare, persistent racial and ethnic disparities in treatment outcomes (despite decades of research) raise pressing questions about bias within both medical research and clinical practice. Acknowledging these failings is not a concession to anti-intellectualism but a necessary condition for epistemic renewal.

Digital Disruption and the Performance of Knowing

Digital platforms have fundamentally altered the production and circulation of knowledge. Comment sections, forums, and social media do not just distribute information—they host performances of identity. Drawing on Goffman (1959), we can see these performances as forms of ‘face work’, where asserting certainty or contrarianism signals autonomy, defiance, or group loyalty. The act of claiming to “know better” becomes less about truth and more about presence and visibility. To know is to exist, and to assert knowledge is to demand recognition.

These dynamics are reinforced by algorithmic design. Sunstein (2009) discusses how digital echo chambers encourage homophily—users encountering views that mirror their own. Algorithmic curation creates an illusion of consensus, where alternative viewpoints are not absent but actively excluded. Bourdieu (1984) would recognise in this a classed distinction: epistemic legitimacy becomes a matter of taste, aligned with identity rather than evidence. As epistemic echo chambers deepen, they shift from passive bubbles to active filters of reality.

Furthermore, the linguistic codes used by experts—often abstract, cautious, and qualified—can feel alienating to those used to more direct or emotionally resonant discourse. This mismatch exacerbates misrecognition. In digital public spheres, it is the force of conviction, not the depth of expertise, that wins attention. Thus, misinformation often appears more confident—and therefore more credible—than legitimate uncertainty.

Covid-19 and the Misreading of Scientific Reflexivity

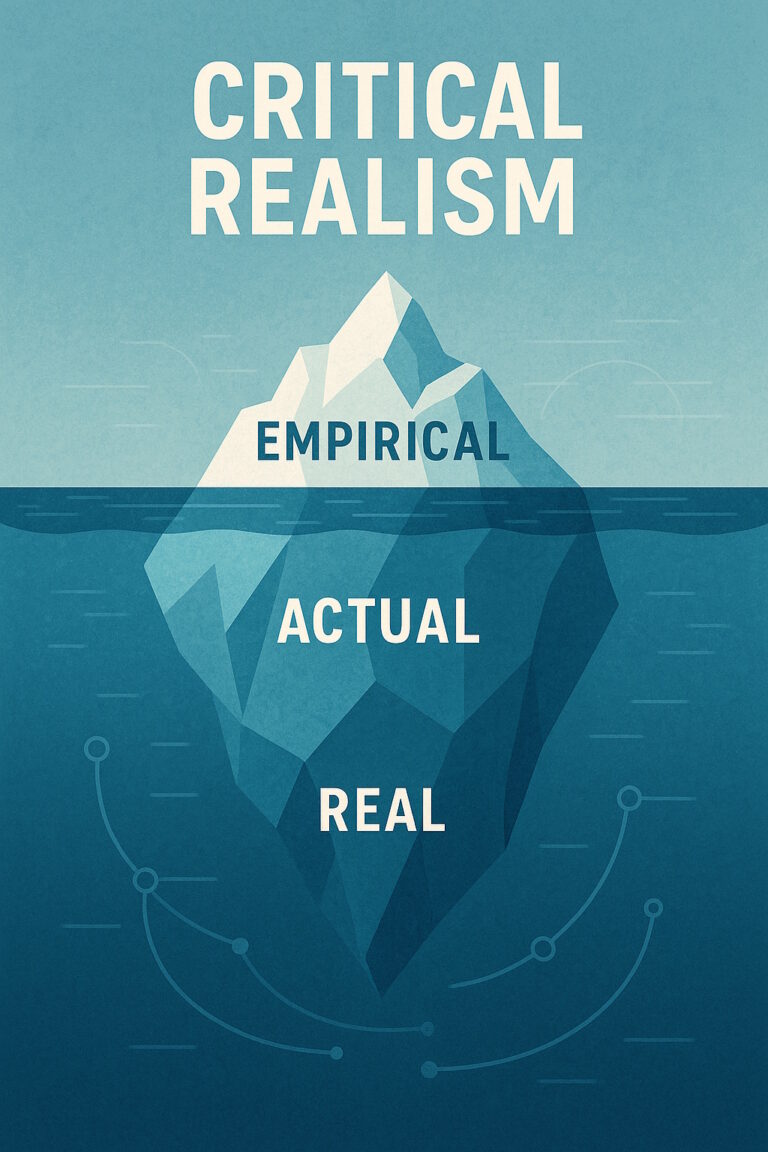

The Covid-19 pandemic revealed the costs of widespread epistemic impatience. Scientific knowledge, inherently provisional, was mistaken for indecision. As Beck (1992) argued, reflexive modernity demands the constant updating of knowledge in response to new risks. Yet many lay observers interpreted changing guidance as incompetence or deceit. The assumption that knowledge must be static, final, and flawless undermines public understanding of science.

This mistrust was exacerbated by political hypocrisy. When public figures flouted the very restrictions they imposed, they undermined the symbolic coherence of the rules. Drawing on Durkheim (1995), we might say the moral authority of those rules was desecrated; they ceased to function as binding social facts. Into this breach flowed conspiracy, cynicism, and the seductive clarity of simplistic narratives that promised certainty amidst crisis.

Conspiratorial claims that Covid-19 was a hoax, a means of population control, or a manufactured bioweapon filled the vacuum left by institutional failure. These narratives were not only shared by the misinformed; they were welcomed by those who felt betrayed or unseen. Their emotional resonance compensated for their factual weakness.

And yet, expert institutions themselves are not immune to failure. Groupthink, epistemic conservatism, and bureaucratic inertia can inhibit timely responses and suppress dissenting voices within professional communities. The slow initial response to airborne transmission of Covid-19, for instance, reflects a reluctance within parts of the medical establishment to revise guidance in light of emerging, though not yet definitive, evidence. A sociology of expertise must therefore be critical not only of its rejection, but also of its reproduction.

When Facts Become Flexible: Truth as Identity Work

Some individuals do not simply reject facts; they remake them to align with personal or group identity. Berger and Luckmann (1966) argued that reality itself is socially constructed—shaped by shared meanings. In digital comment spaces, this becomes hypervisible. Commenters routinely insert pet grievances—net zero, immigration, perceived cultural decline—into unrelated debates. These interjections are not merely digressions; they are expressions of epistemic control, assertions that one’s worldview is not only valid, but dominant.

This poses a challenge: are these individuals wrong? Empirically, often yes. But sociologically, their epistemic defiance is not meaningless. It is a response to marginalisation, a way of reclaiming agency in a world perceived as dismissive or hostile. As Cohen (1972) showed in his work on moral panics, deviant narratives serve psychological and social functions. They provide order in a context of perceived disorder. The spread of “alternative facts” is thus not just informational but therapeutic.

The act of expressing distorted beliefs—such as denying climate science or accusing political figures of fabricated crimes—is performative. It is not about persuading others, but about asserting presence and gaining symbolic capital within one’s own epistemic community. Within these circles, fidelity to the group’s narrative matters more than fidelity to observable reality.

The Platform Problem: Dismantling of Epistemic Infrastructure

Compounding this crisis is the active dismantling of mechanisms designed to protect epistemic integrity. The removal of fact-checkers from platforms like Facebook and X represents more than a cost-cutting measure; it is a withdrawal from public responsibility. Foucault (1980) reminds us that power and knowledge are inextricably linked. To abdicate fact-checking is to surrender the power to shape public discourse to those with the most reach, not the most reason.

The disappearance of epistemic guardrails shifts the burden of discernment onto individual users, many of whom lack the time, tools, or training to evaluate competing claims. In this context, misinformation does not just survive—it flourishes. It becomes self-reinforcing, embedded in both platform logic and group identity. Outrage and virality replace evidence and expertise. The result is a public square where truth is not debated, but out-shouted.

Towards Reconstructive Dialogue: Sociological Responses

What, then, can be done? First, institutions must rebuild trust not by demanding deference, but by fostering reciprocity. Coleman (1990) conceptualised trust as social capital—earned through consistent, credible engagement. Experts must become more embedded, not just more visible. They must engage in dialogue, not just dissemination.

Second, we need a pedagogy of epistemic humility. Freire (1970) proposed dialogue, not transmission, as the foundation of learning. This model acknowledges the value of lived experience while maintaining the distinctiveness of expertise. It resists the flattening of knowledge hierarchies without abandoning the need for rigour. Experts can admit uncertainty without ceding authority.

Third, digital design must become ethically responsive. As Tufekci (2017) and others have shown, the architecture of online spaces shapes what is seen, shared, and believed. Platforms must prioritise epistemic responsibility alongside profit, integrating transparent algorithms and restorative moderation strategies. This includes reinstating forms of fact-checking that do not censor, but contextualise.

Finally, public education systems must include epistemic literacy: teaching how knowledge is formed, revised, and legitimised. Only through such foundational education can citizens be empowered to navigate a fragmented and contested epistemic landscape.

Contested Knowledge, Reimagined Authority

The “death of expertise” is not a sudden event, but the culmination of long-standing structural exclusions, cultural misrecognitions, and technological amplifications. While many of those who reject expert authority are empirically wrong, their resistance is often a rational response to a world in which they feel unrecognised or unheard. The task, then, is not to restore deference, but to cultivate legitimacy: through dialogue, through humility, and through a sociologically informed reconfiguration of how we understand and share knowledge.

Rebuilding trust in expertise does not mean silencing dissent. It means transforming the social conditions in which dissent emerges. It requires institutions that listen, platforms that care, and publics that are invited into the epistemic process—not as passive recipients, but as legitimate participants. In such a world, expertise will not need to demand trust; it will deserve it.

References

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity (M. Ritter, Trans.). SAGE.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

- Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: The creation of the Mods and Rockers. MacGibbon and Kee.

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press.

- Durkheim, E. (1995). The elementary forms of religious life (K. E. Fields, Trans.). Free Press. (Original work published 1912)

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977 (C. Gordon, Ed.). Pantheon Books.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

- Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Republic.com 2.0. Princeton University Press.

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press.

- Tyler, I. (2013). Revolting subjects: Social abjection and resistance in neoliberal Britain. Zed Books.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). University of California Press.