If you’re a sociology student and you’ve ever stared blankly at the words ontology and epistemology, wondering if you’d accidentally wandered into a philosophy degree—you’re not alone. When I was an undergraduate, I found these concepts mystifying. It often felt as though everyone else in the seminar room had access to some secret intellectual code while I was still struggling with the terms themselves. And I know from experience—as a researcher now specialising in education and sociology—that this confusion is not unusual.

Yet despite their intimidating labels, these two ideas are central to everything we do as sociologists. They shape not only what questions we ask, but how we interpret the world around us. Understanding them isn’t about memorising jargon or impressing supervisors; it’s about learning how to think critically about the assumptions we all carry into our work. And the earlier you begin to grasp them, the more confident—and consistent—you’ll be as both a student and a sociological thinker.

This article breaks down these foundational terms in plain language, with examples from real-world research and social issues. If you’ve ever asked yourself What counts as reality? or How do we know what we know?, you’ve already started thinking ontologically and epistemologically. Now it’s just a matter of giving those thoughts the right names—and learning how to use them with intent.

Understanding Ontology: What Are We Claiming Exists?

“Ontology is about what we believe is real in the world—and whether that reality exists independently of us or is shaped by us.”

Ontology, in the context of research, is about what we assume exists in the social world. It asks: What is the nature of reality? What kinds of things are we studying, and do we believe they exist independently of our observation? These questions may sound abstract at first, but they are deeply practical. Every time a sociologist sets out to study a social issue—whether inequality, identity, or institutional power—they are making ontological choices, often without even realising it.

At its simplest, ontology concerns itself with what is real, and how that reality is structured. For example, do we believe that ‘class’ is a tangible social structure that exists regardless of whether people are aware of it (a realist position)? Or do we see it as something constructed through discourse and interpretation, only existing because we talk and act as if it does (a constructivist position)?

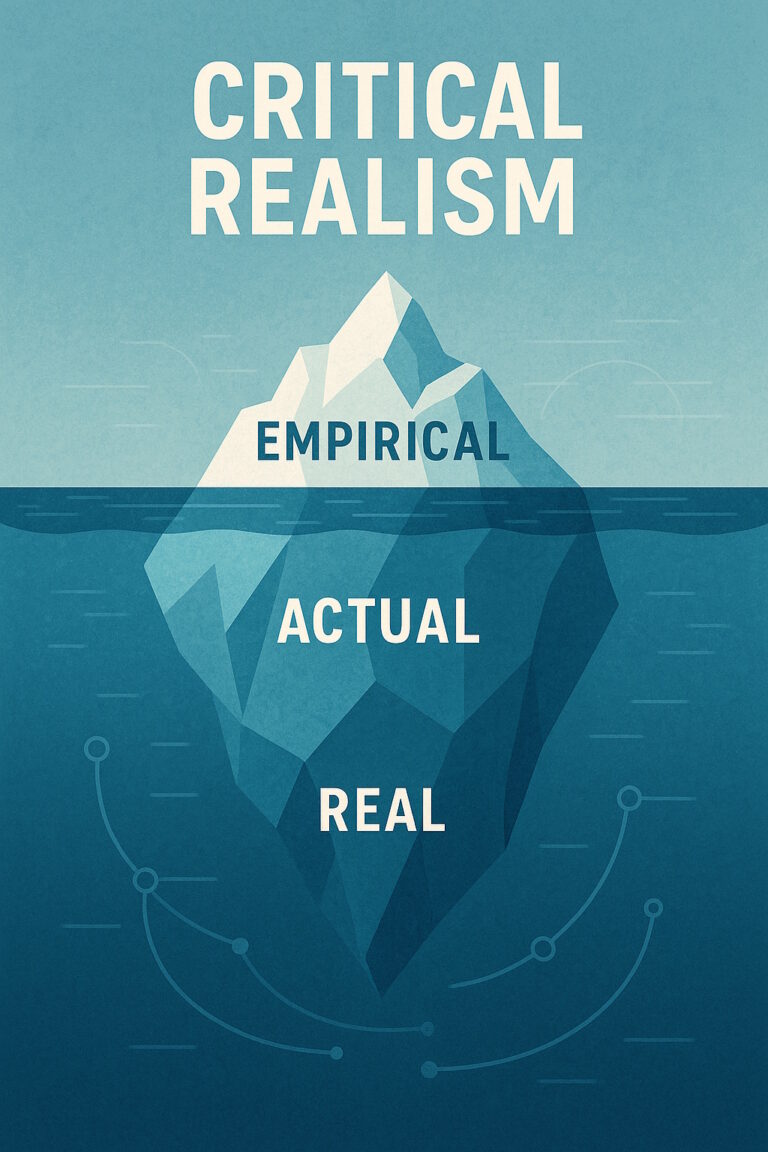

Sociologist and philosopher Roy Bhaskar (1975, 1979), the key figure in critical realism, argues for a stratified view of reality. He suggests that the social world has real structures—like capitalism, patriarchy, or education systems—that exist and exert influence even if we can’t directly observe them. These structures are not fixed or deterministic, but they shape the possibilities available to individuals.

In contrast, constructivist or interpretivist ontologies argue that social reality is made through human interaction and meaning-making. In this view, race, gender, and class are not “real” in the same way that gravity is, but are constructed through language, practice, and power relations (Guba & Lincoln, 1994; Blaikie, 2007).

Many sociologists adopt a layered or hybrid stance, recognising that some structures are relatively enduring while others are fluid and negotiated. My own approach aligns with critical realism: I believe that social structures exist and shape lives, but I also acknowledge that individuals navigate these constraints in diverse, context-specific ways (Crotty, 1998).

Understanding Epistemology: How Do We Know What We Think We Know?

“Epistemology is about how we come to know the world—and what kinds of knowledge we consider trustworthy, valuable, or valid.”

If ontology is about what we assume exists, epistemology is about how we come to know it. Epistemology asks: What counts as knowledge? How do we decide what is valid, reliable, or meaningful?

Crotty (1998) explains that epistemology shapes our entire research approach—whether we trust in observable facts and statistics, or whether we believe that understanding comes from people’s experiences and interpretations. It’s not just about methods; it’s about what we value as knowledge.

Positivism

Positivism holds that knowledge should be derived from observable, measurable facts. Social reality, in this view, behaves according to laws that can be discovered through empirical observation. This approach underpins many quantitative methods but has been criticised for oversimplifying human complexity (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Interpretivism

Interpretivism sees reality as constructed through social interaction and meaning-making. Knowledge arises from understanding how people interpret their worlds. It supports qualitative methods such as ethnography, interviews, and case studies.

Critical Epistemologies

Feminist and standpoint epistemologists argue that knowledge is shaped by social position. Harding (1991) suggests that marginalised groups often have critical insights into structures of power. Bourdieu (1990) similarly argues that researchers must reflect on their own social position to understand how it shapes the knowledge they produce.

What Is a Research Paradigm?

“Your paradigm reflects how you see the world—and how you choose to make sense of it.”

A research paradigm is a framework that combines your ontological and epistemological assumptions with your values, methodology, and aims as a researcher. It’s the intellectual scaffolding that supports your approach to knowledge. Paradigms are not just philosophical—they shape what questions you ask, how you collect data, and how you judge the success of your findings.

Some common research paradigms in sociology include:

- Positivism – reality exists independently; knowledge is objective; emphasis on measurement and generalisability.

- Interpretivism – reality is socially constructed; knowledge is subjective and contextual; emphasis on depth and meaning.

- Critical theory – reality is structured by power; knowledge is political; emphasis on emancipation and reflexivity.

- Pragmatism – reality is plural and flexible; knowledge is what works in practice; emphasis on solving problems.

Can You Mix Paradigms? On Flexibility and Pragmatism

Many students (and researchers) find themselves drawn to different methods for different reasons. This leads to the question: Can I mix qualitative and quantitative approaches?

The answer is yes—but with care. Methodological pragmatism allows researchers to combine tools across paradigms to suit their research questions. A mixed methods study might, for example, pair surveys with interviews to explore both breadth and depth.

However, blending methods requires philosophical clarity. It’s not enough to just bolt two methods together; you must understand how their underlying assumptions align or diverge. Blaikie (2007) and Guba & Lincoln (1994) caution that uncritical mixing can lead to incoherence—using tools designed for different worldviews without considering their fit.

That said, many scholars argue that rigid paradigm boundaries are increasingly outdated. As long as your research design is well-justified, theoretically aware, and methodologically coherent, a flexible approach is defensible.

“Mixed methods can work—but only when your philosophical assumptions are as integrated as your tools.”

Bringing It Together: Ontology and Epistemology in Practice

“Ontology is the map of the terrain; epistemology is how you decide to explore it.”

Ontology and epistemology are not just abstract concepts for textbooks—they’re tools for thinking about how we see the world and how we choose to study it. Your ontology influences your epistemology: if you believe social reality is fixed and structured, you may be drawn to positivist methods. If you see it as fluid and co-constructed, you might favour interpretive ones.

Understanding these terms helps you build a coherent research project and a defensible methodology. It also makes you a more reflexive thinker—aware of the assumptions guiding your work and better able to critique the assumptions in others’.

Tips for Students

- Ask: What do I think is real here?

- Match your methods to your beliefs about reality and knowledge.

- Be consistent, but also flexible—sometimes our positions evolve.

- Use theory to support your stance, but explain it clearly and plainly.

- Remember: this isn’t just philosophy—it’s the foundation of good sociological thinking.

“Being clear about your ontology and epistemology won’t just help your essays—it will make you a better sociologist.”

Where to Go for More Help

If you’re still unsure about how ontology and epistemology relate to your own work, don’t worry—you’re not alone. These are complex ideas that even advanced researchers continue to refine and debate.

A good starting point is your university’s Subject Librarian for sociology or social sciences. They can help you find resources tailored to your course level, suggest key texts that explain philosophical assumptions in accessible ways, and guide you toward research examples that illustrate different paradigms in action.

You might also consult your module guide, supervisor, or research methods tutor. Don’t be afraid to ask questions—clear thinking begins with conversation.

“Clarity grows through curiosity—don’t hesitate to ask for guidance.”

References

- Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science. Leeds Books.

- Bhaskar, R. (1979). The possibility of naturalism: A philosophical critique of the contemporary human sciences. Harvester Press.

- Blaikie, N. (2007). Approaches to social enquiry: Advancing knowledge (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). In other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology (M. Adamson, Trans.). Polity Press.

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. SAGE.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). SAGE.

- Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? Thinking from women's lives. Cornell University Press.