For students starting out in sociology, one of the first challenges is learning to think about the social world in a deeper, more structured way. It’s not just about describing what we see around us, but about understanding why things happen the way they do, and how different social forces interact to shape our lives. This is where critical realism comes in. Developed by the British philosopher Roy Bhaskar in the 1970s, critical realism offers a powerful framework for connecting the ‘big picture’ of social structures with the everyday actions of individuals (Bhaskar, 1975). It helps us see beyond the surface of social life, revealing the often hidden forces that influence our choices, opportunities, and social outcomes.

Foundational Principles of Critical Realism

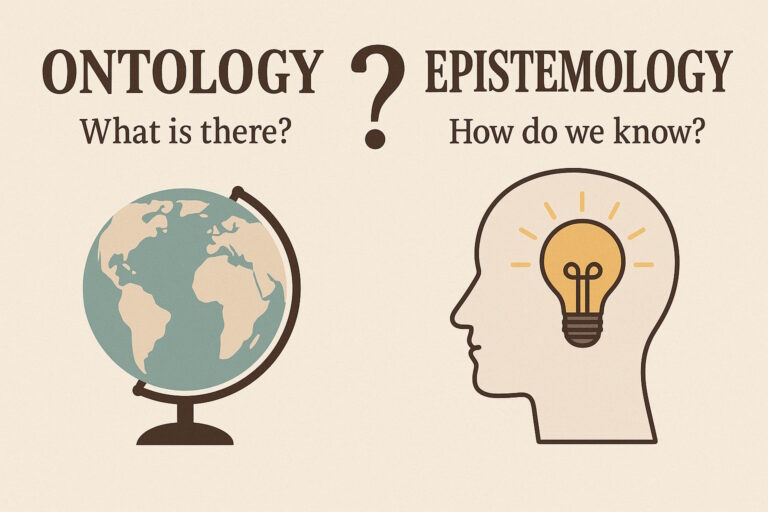

Critical realism is built on a few key ideas that set it apart from other approaches in the social sciences. These include a layered understanding of reality, the concept of emergence, and a focus on uncovering the often hidden processes that drive social change (Bhaskar, 1979; Archer, 1995).

Stratified Ontology

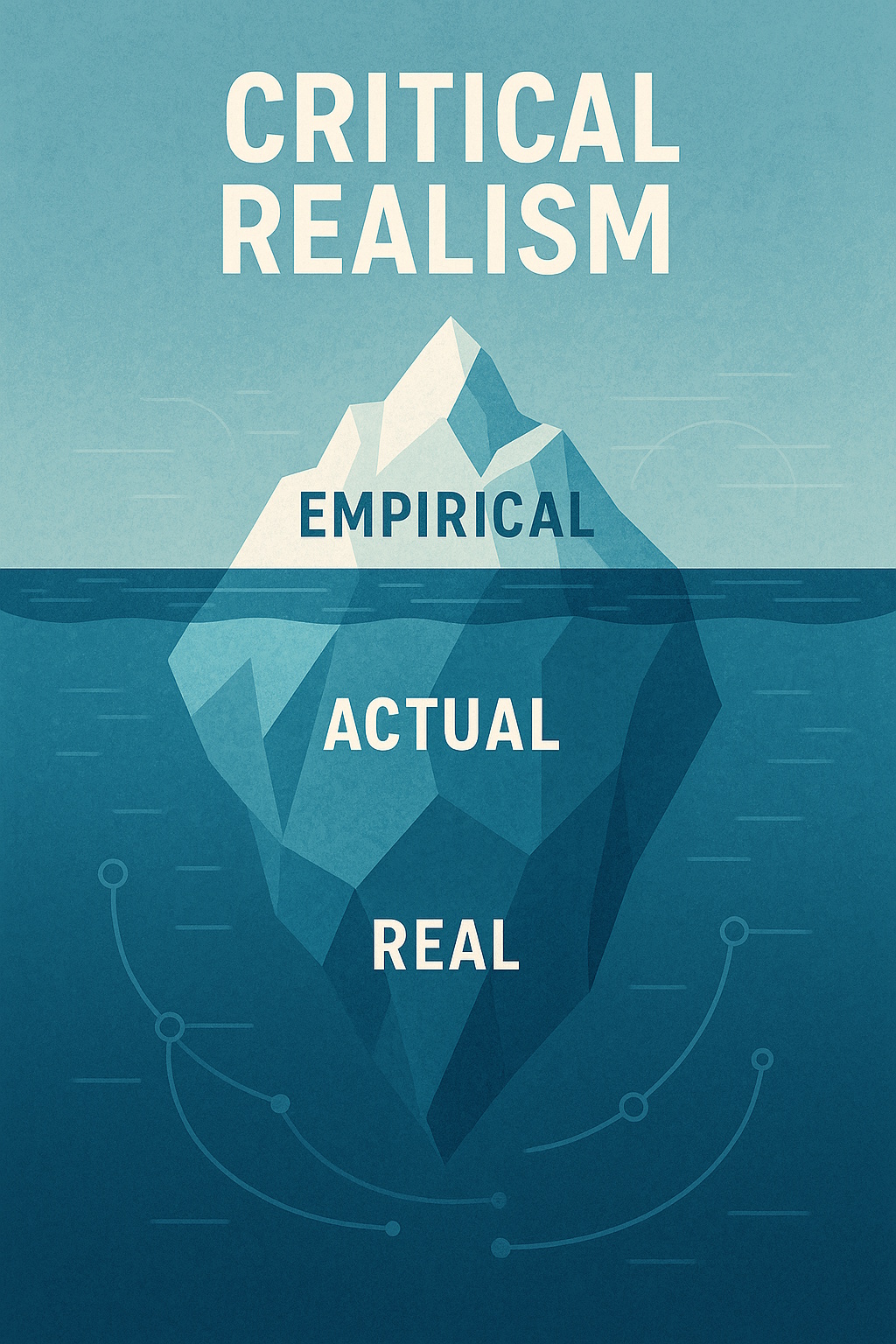

At the heart of critical realism is the idea that reality is layered. This means that what we see and experience on the surface is often just one part of a much more complex system. Critical realists argue that the social world is made up of three different levels (Bhaskar, 1978):

- The empirical domain: what we can directly see, hear, and measure – our experiences and observations. For example, when you walk into a classroom, you can see the desks, hear the lecturer, and observe your fellow students.

- The actual domain: everything that happens, whether we observe it or not. This includes the conversations in the corridors, the interactions in group projects, and the quiet studying that happens in the library – even if no one is recording it.

- The real domain: the underlying structures and mechanisms that cause things to happen and give rise to patterns in social life. In the context of a university, this might include the policies that shape teaching practices, the economic pressures that influence student behaviour, and the cultural expectations that define what it means to be ‘educated’ (Archer, 1995).

Emergence and Generative Mechanisms

Another key idea in critical realism is emergence – the idea that social systems are more than just the sum of their parts (Archer, 1995; Elder-Vass, 2010). For example, a university is not just a collection of buildings, students, and teachers. It has its own culture, norms, and power dynamics that shape the experiences of those within it. These ’emergent’ properties can have powerful effects. For instance, the reputation of a particular university can shape students’ career prospects long after they graduate, influencing their social status and economic opportunities in ways that go far beyond their individual academic performance (Elder-Vass, 2010).

Central to this idea is the concept of generative mechanisms – the hidden processes that make things happen in the social world. These mechanisms operate at the ‘real’ level, shaping the events and interactions that we can observe (Bhaskar, 1978). For example, economic inequality is not just about differences in income. It also involves deeper, often hidden forces like the education system’s role in reinforcing class divisions, the impact of housing policies on wealth distribution, and the influence of corporate lobbying on economic regulation (Sayer, 1992).

Structure, Agency, and Reflexivity

Critical realism is also deeply concerned with the relationship between structure and agency – the ongoing tension between the social structures that shape our lives and the ways in which we respond to them (Archer, 2003). While social structures profoundly influence individual actions, critical realists argue that people still have some capacity to act independently. This is where the concept of reflexivity comes in. Reflexivity is the ability to reflect on our social context and make deliberate choices within it. For instance, a student from a disadvantaged background might choose to push back against the low expectations placed upon them, finding creative ways to succeed despite structural barriers (Archer, 2003).

Open Systems and Methodological Implications

Critical realism also recognises that the social world is an open system – a complex, ever-changing network of relationships that cannot be fully understood through simple cause-and-effect thinking (Bhaskar, 1979). Unlike the closed systems studied in the natural sciences, social systems are shaped by multiple, overlapping forces that produce unpredictable outcomes. This means that research methods based on critical realism often focus on identifying the underlying structures and mechanisms that shape social life, rather than just describing surface-level patterns (Sayer, 1992).

Alternative Theoretical Approaches

While critical realism offers a powerful framework for understanding social life, it is not the only option for social researchers. Other approaches include:

- Positivism: Focuses on finding general patterns and statistical regularities but often overlooks deeper social structures (Durkheim, 1895).

- Interpretivism: Emphasises the meanings people attach to their experiences but can miss the broader social forces shaping those experiences (Weber, 1922).

- Post-Structuralism: Highlights the fluid, contested nature of social reality but often lacks a coherent account of enduring social structures (Foucault, 1977).

- Constructivism: Focuses on how social reality is built through interaction but may struggle to account for broader systems of power and inequality (Berger & Luckmann, 1966).

The Ongoing Relevance of Critical Realism

For students of sociology, critical realism is a valuable tool for making sense of a complex world. It encourages us to look beyond the obvious, to question simple explanations, and to dig deeper into the hidden forces that shape social life. By recognising the layered nature of reality, critical realism helps us connect everyday experiences with broader social structures, revealing the often unseen mechanisms that drive change and maintain power.

As you move through your studies, this approach can help you think more critically about the social world – from the impact of educational systems on social mobility to the ways in which economic policies shape everyday life. It’s a way of thinking that not only asks what happens, but also why and how, encouraging a more thoughtful, reflective approach to understanding society.

In a rapidly changing world, where social structures are constantly shifting and new challenges are emerging, critical realism remains a vital framework for those looking to understand the deeper currents of social change.

References

- Archer, M. (1995). Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bhaskar, R. (1975). A Realist Theory of Science. London: Verso.

- Bhaskar, R. (1979). The Possibility of Naturalism. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Danermark, B., Ekström, M., Jakobsen, L., & Karlsson, J. (2002). Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Sayer, A. (2000). Realism and Social Science. London: SAGE Publications.